In the final three months of 2019, I participated in the Arcus studio residency. Situated in the bedroom community of Moriya Japan, I was within commuting distance of the Metabolist structures and built environment engineered for the Tokyo Summer Olympic Games of 1964. And as I explored these sites, I encountered the politically contentious stadium architecture nearing completion for the (soon to be ill-fated) Summer games of 2020.

The outcome of the site based research revealed a post-Second War landscape characterized by experimental architecture and urban planning, advanced in part through new applications of concrete and a triad power structure of state, corporation and construction. It was equally a period of rapid and sometimes violent modernization; a time of huge mobilization marked by great social and spatial upheaval.

By contrast, the national discourse of 2019 hedged toward the glories of past accomplishments. This was realized in two ways; as commemoration of the 1964 games, and secondly, as nostalgia for utopian images. Yet the shift toward an idealized history was not by accident. By 2019, murmurings critical of the Olympics had begun to gather in resonance, with many openly questioning why Tokyo had been chosen as a host city for the games. Why, for example, allocate public finances toward a nationalist spectacle and transnational corporation, when efforts were still ongoing to mitigate the effects of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami? Or more broadly, why expend millions of yen to attempt signature architectural pieces like a Zaha Hadid stadium, when the effects of the lost decades from the millennial recession were still being felt? By 2020, objections to the games became impossible to ignore as the Covid-19 pandemic pushed most of the world into quarantine and lock down. With headlong determination, the IOC (International Olympic Committee) laid bare much of their motivations by insisting the games proceed uninterrupted and on schedule. Only after considerable domestic and international pressure, with participating countries threatening to withdraw athletes from competition, did the IOC relent and postpone the games until the summer of 2021. All the while, the pandemic raged.

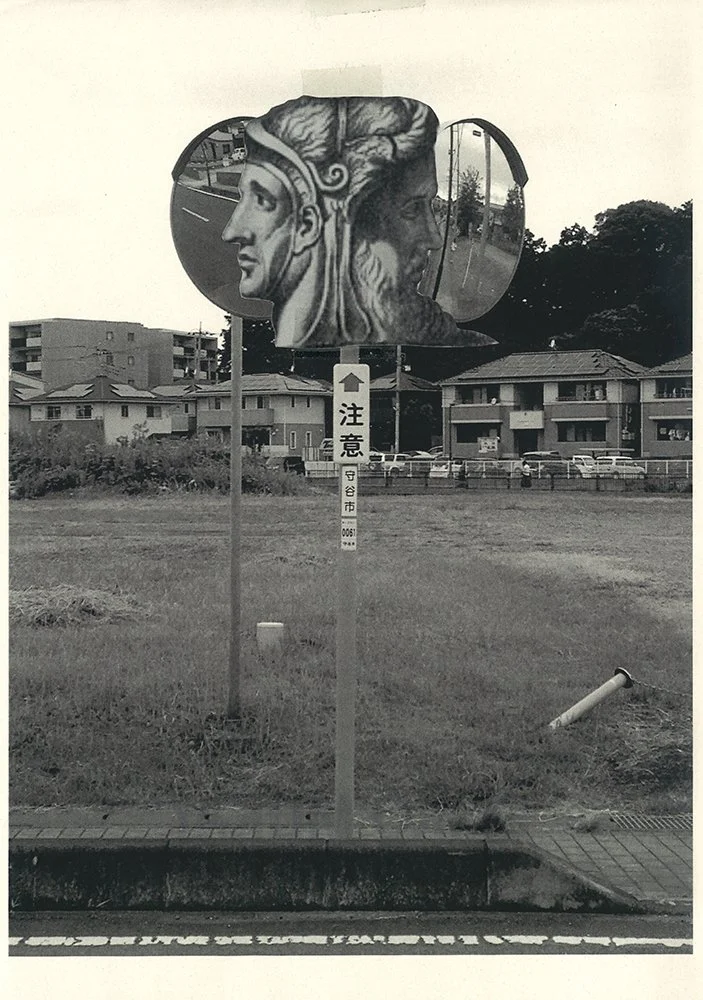

But in 2019, what I observed in the preparations gathering pace, was both a willful turn to the past and an avoidance of the exigencies of the present. Or put another way, it was the present being played as fantasy, an engineered event caught between a past that had never really taken place and a future that had failed to fully arrive. Time was out of joint, stuck in a feedback loop without a point of origin or destination. Like being caught between two opposing mirrors.

By the conclusion of the residency, I had scaled the upper levels of a stadium in the Ibaraki prefecture, toured an artificial island created from the impacted garbage of Tokyo and interviewed academics and historians. Concurrent to these activities, I worked in the studio, translating some of the outcomes of the site based research into what would become an installation. Central to my activities was the collection and allocation of water throughout the studio. Weeks prior, I had affixed a small, battery powered dehumidifier to the front of a three speed bicycle that was too small for me to comfortably ride. Still, I used this bicycle to explore the community of Moriya and its surrounding environs, and as I pedaled through fields left fallow for the winter, shopping centers and tracts of housing, water was pulled from the moisture rich air. I returned to the studio with the water, where it filled ceramic pots carefully placed throughout the space.

The pots had also been collected; sourced from a small community of retirees that regularly gathered to meet in a ceramics studio near to the residency. I was invited into their homes to share tea, discuss their life, their former careers and together, to make a selection from the ceramic objects that they had made.

The group shared more than an interest in ceramics; now in their late 70’s to early 80’s, they were all of the same generation, with first hand experience of the 1964 Summer Olympic games. The ceramic pots that we chose together, were an extension of each artist and a continuation of a life’s history. A line could be drawn, connecting the events of the 1964 Olympics to the clay that had been formed and shaped. The inclusion of the pots felt like a counterpoint to the monumental stadiums and architecture that I had visited; boundless histories rendered on an intimate scale.

Ceramicists that make pots will use a unique symbol to sign the bottom of their work. But unless each pot is handled, picked up and turned over, the marks go unseen and the artist’s identity unknown. It was important that each artist’s identity remain legible; more so, that they be given a physical presence in the installation. Each pot was an accounting, standing in as a proxy for the artist. I photographed the marks on the bottom of the pots and created UV prints on aluminum panels. The panels and pots were placed on cork lined platforms low to the floor, creating delimited surfaces to contemplate the relation between the two.

A second, stationary dehumidifier was placed in the classroom to re-collect the water as it evaporated from the ceramic vessels over the duration of the open studio. This water was returned to the ceramic vessels, creating an uninterrupted flow of water, and an idea of historical events returning within the exhibition.